The decisive factor isn’t his ads or charisma. It is the public financing of election campaigns, and it should be replicated across the United States.

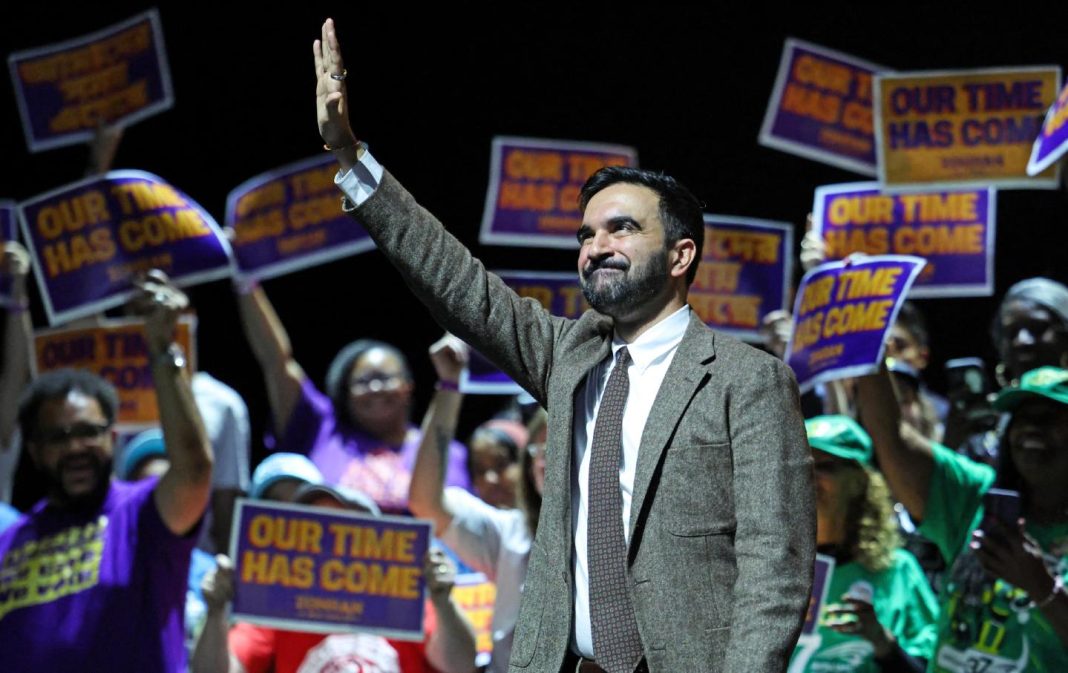

New York City Democratic mayoral candidate Zohran Mamdani waves after speaking during a rally in Washington Heights, New York on October 13, 2025.

(Charly Triballeau / AFP via Getty Images)

In the final days before New York’s mayoral election, every politico and news junkie seems to be looking for a lesson in Zohran Mamdani’s rise. How exactly did an obscure legislator overcome the collective power of the political establishment, win New York City’s Democratic primary, and become the general-election frontrunner to lead the United States’ largest city?

Those looking to replicate his success want to know: Was his secret sauce the super-slick ads? Was it his populist message spotlighting the city’s affordability crisis? Was it his uncanny ability to draw attention to himself? Or was it his sunny charisma and energetic youth in an age of decrepit gerontocracy?

All of these factors undoubtedly contributed to Mamdani’s shocking ascent, but most of those positives might never have mattered absent the most significant but least discussed factor of all: public money.

Thanks to New York City’s nearly four-decade-old clean elections system that publicly finances candidates for municipal office, Mamdani has had nearly $13 million of government funds to run a competitive campaign against tens of millions of dollars that oligarchs spent to boost disgraced Democratic former governor Andrew Cuomo.

Without that public money matching small-dollar donations to Mamdani’s campaign, he might never have had enough resources to finance his reported $5 million television and digital ad campaign that spread his message, his $1 million of mail and literature that made him a household name, and his $2 million campaign staff that organized communities and flooded the social-media algorithm.

In other words, even with Mamdani’s skills and vision, without public money, it’s a good bet he never would have been able to raise enough resources to make sure voters knew who he was, saw his charisma in action, and heard about his agenda.

This inconvenient truth runs counter to the fairy tales that pundits, activists, and armchair strategists love to manufacture—the romantic myths about campaigns being won purely through idealism, grassroots energy, strong messaging, likeable candidates, and shrewd Moneyball-style tactics, cash be damned.

That might be a wonderful society, but it’s not the one we live in. Indeed, anyone who has run for office or worked on a campaign knows that without competitive resources, even the best candidates with the most compelling messages simply cannot reach voters to make them aware they exist. Without public funding, such resources aren’t typically available to candidates who campaign on promises to challenge the oligarchs and corporations that typically bankroll campaigns.

“It’s incredibly important,” Mamdani told The Lever when asked about how integral public money has been to his campaign’s success. “What it allows is the amplification of the voice of ordinary New Yorkers, as opposed to the billionaires who have grown used to buying our elections.”

So the biggest lesson in Mamdani’s race is that—regardless of your political party or ideology—if you want candidates who come from outside the system and aren’t puppets of big donors and corrupt political machines, then you should get behind the nonpartisan movement to publicly finance the elections in your community, your state, and your country.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →

“The Need For Collecting Large Campaign Funds Would Vanish”

Public campaign finance systems provide candidates a way to run for office that does not force them to fund their campaigns with money from private donors seeking policy favors. These systems offer government funds to candidates who qualify and who then follow some basic rules.

Some of these systems like New York’s offer matching funds for small dollar donations, essentially supercharging the financial power of grassroots donations. Others offer grants to candidates after they prove community support by collecting a certain number of small contributions. Candidates are not compelled to participate—but those who do are barred from spending any more money than they receive from the system. Publicly financed candidates can, like Mamdani, still face well-financed attacks from outside super PACs, but the systems at least give those candidates competitive resources to fight back.

The notion of publicly funding campaigns might at first seem new, weird, and politically unrealistic, but it is actually old and simple. What’s more, federal lawmakers have come vanishingly close to creating a public financing system at the national level in the past—and such systems also operate in various communities throughout the country.

The idea was first proposed by Teddy Roosevelt in 1907 amid rampant Gilded Age corruption.

“There is a very radical measure which would, I believe, work a substantial

improvement in our system of conducting a campaign,” Roosevelt wrote in his annual message to Congress that year. “The need for collecting large campaign funds would vanish if Congress provided an appropriation for the proper and legitimate expenses of each of the great national parties, an appropriation ample enough to meet the necessity for thorough organization and machinery, which requires a large expenditure of money.”

After the Nixon White House tapes and the Watergate investigation exposed corporate money being secretly funneled into Republican coffers amid executive branch favors, Congress passed a law offering public financing to qualifying presidential candidates. In 1973, the US Senate also passed legislation to publicly finance congressional campaigns—but the bill was blocked in the Democratic-controlled House.

Nearly two decades later, in the wake of the Keating Five and Savings and Loan scandals, both houses of Congress passed public financing legislation in 1992, but Republican president George H.W. Bush vetoed it. His Democratic successor Bill Clinton soon after pushed a public financing bill, but Republicans successfully filibustered it—just before winning Congress and killing the idea for another generation.

By the time 2008 rolled around, Barack Obama started the trend of presidential candidates opting out of the public financing system because they perceived its spending limits to be too strict. The fund has been rendered effectively defunct—and is being targeted for elimination by Republicans—as big donors and super PACs now routinely buy races for the White House.

Despite those setbacks, however, 14 states and 26 localities of varying partisan complexion have set up public financing systems in their own elections. In Connecticut, Arizona, New York state, and New York City, these systems were created as a direct response to egregious corruption scandals. Amid today’s incessant corruption scandals, California voters will soon decide whether to lift their state’s ban on public financing of campaigns. Meanwhile, there is now Democratic legislation in Congress aiming to begin putting the concept back into the national conversation if Democrats ever regain congressional majorities to pass it.

The beauty of public financing is that because it does not limit spending, it does not run afoul of the Supreme Court’s precedents equating money with free speech. In fact, a year after the 2010 Citizens United ruling, the Roberts Court wrote: “We do not today call into question the wisdom of public financing as a means of funding political candidacy.”

As the Brennan Center’s Ian Vandewalker recently put it: “Public financing is the most effective and powerful reform because we can’t stop super PACs and rich donors from spending as much as they want, but we can sort of lift everybody else’s voices up with matching funds.”

The Celebrity Lane Is Not Available To Most Candidates

Of course, a handful of high-profile politicians funded by grassroots donations from across the country might look like proof that for all its flaws, the current campaign finance system works and therefore public financing systems aren’t necessary.

And it’s true: Political celebrities like Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders, New York Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, Maine Senate candidate Graham Platner, and Michigan Senate candidate Abdul El-Sayed have succeeded in raising their profiles to the point where they can tap into a national grassroots donor base, which allows them to avoid the corrupt and transactional world of big-dollar pay-to-play fundraising.

But the problem for most down-ballot anti-establishment candidates, whether Democrat or Republican, is that the celebrity lane is not replicable.

They will never be able to become viral Internet stars, and they aren’t running in races whose national implications inherently interest grassroots donors in faraway locales. And most of them will never be AOC pulling the lottery ticket of social media stardom by defeating an incumbent in a once-in-a-lifetime upset that just so happened to take place in the capital of the global media—a perfect storm that vaulted her to international fame.

Instead, most of America’s elections—including many that are as or more important than congressional contests—are occurring in down-ballot races, often in heartland news deserts, where there is barely any local, much less national, media.

Inside that vacuum, most candidates will never be able to TikTok their way to local voter support or attention-freak their way to virality. Likewise, most candidates will never be able to pithily tweet their way into the national grassroots fundraising machine necessary to compete with oligarch and corporate cash funding television ads and direct mail. (Sidenote: Is social-media exhibitionism really the skill we want elections to preference when we’re choosing local officials making life-or-death community decisions?)

That leaves most prospective candidates for public office trapped inside the current privately financed system. Save for the rare non-celebrity exceptions somehow able to scratch together local grassroots money, most candidates in the private system end up facing a terrible choice: Either run idealistic power-challenging races at great risk of never raising enough resources to compete, or sell out to favor-seeking big donors in exchange for a lavishly bankrolled but inherently compromised campaign that amplifies oligarchs’ policy agenda.

The most electorally successful politicians inside the privately financed systems almost always choose the latter path of least resistance, which is why wildly popular anti-oligarch policies are so rarely enacted, why the political discourse constantly blames everything other than the donor class for society’s ills, and why studies show that government at all levels mostly represents the interest of wealthy campaign contributors.

An Investment In Our Democracy

Public financing provides an alternate path: It is a way for non-rich, non-celebrity candidates to run competitive campaigns without relying on private cash that comes with the expectation of legislative favors.

“When I ran for state representative, I challenged a 23-year incumbent. I was a social worker and a nonprofit leader, not exactly flush with cash,” recounts Connecticut State Representative Jillian Gilchrest (D). “The reason I had a shot was because of Connecticut’s public financing system, the Citizen’s Election Program. I raised small-dollar donations from people in my district to qualify for a grant that helped me reach voters and share my message. I won. So have many of my coworkers in the legislature who never had deep-pocketed connections or personal wealth… Public financing made it possible. It leveled the playing field.”

Gilchrest is now running in a Democratic primary for the US House on a pledge to champion a bill that would publicly finance congressional campaigns. Corporate CEOs, billionaires, lobbyists, and all the other winners in the current campaign finance system will almost certainly try to defeat such legislation and any other bills like it.

They will probably cite New York Mayor Eric Adams donors’ alleged attempts to defraud his city’s system as proof public financing regimes are riggable—even though public officials successfully caught the scheme. Opponents will also likely portray public financing as wasteful welfare for politicians, insisting that the $14 billion price tag of national federal elections is too expensive.

But under the current system, oligarchs are getting the best government they can buy. For a relatively small investment of their wealth, they get a huge return: They get to purchase a multitrillion-dollar federal government and use its awesome power to help make them even wealthier. The rest of us get a society in which the “preferences of the average American appear to have only a miniscule, near-zero, statistically non-significant impact upon public policy,” as Princeton researchers found.

If we want that to change, we need a lot more elected officials who come from outside the current corrupt system. For that to happen, Mamdani and New York City prove that we don’t just need better candidates, slicker ads, stronger messaging, and more rhetorical odes to democracy.

We also must start using public money to financially invest in that democracy as if we truly value it—and know that our future depends on it.