Over a year after Diron Kelly faced down the judge at his eviction hearing, he still remembered her question: “How did you get to court?”

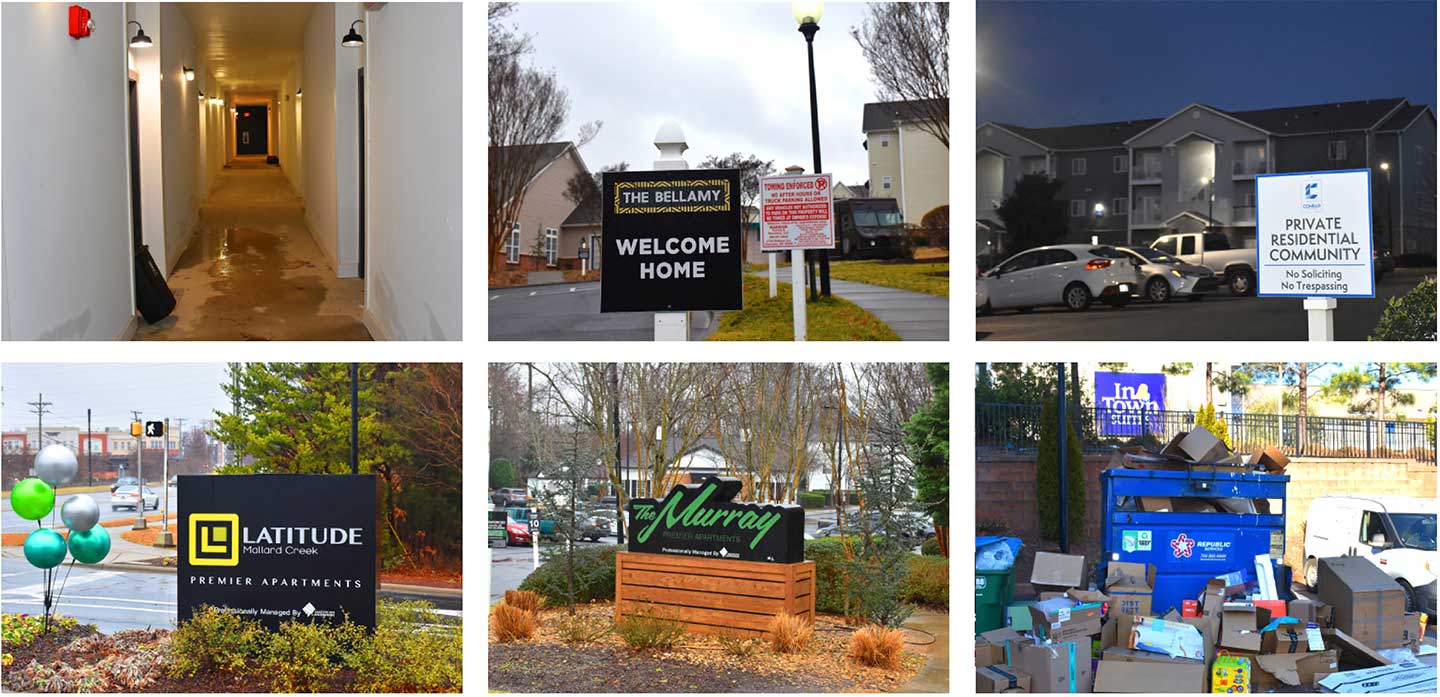

He could have told her about the company that bought Conrad at Concord Mills, the Charlotte, North Carolina, apartment complex where he lived, in March 2022—the one that Kelly says installed a slew of “gadgets” he didn’t need before raising his rent by nearly $400 a month. He could have told her about the eviction notices that the company kept filing against him—the ones that came, he says, with an onslaught of fees that virtually guaranteed he’d never fully get back on his feet.

He could have told her about the trucking accident that tore up his leg just two weeks prior, causing him to need help just to get from his parked truck into the courtroom. He could have told her he put himself through it because he had nowhere else to go.

But in the eyes of the court, it didn’t matter: He owed money that he didn’t have. So he was thrown out in May of 2024 and spent the following months homeless, showering at rest stops, sleeping in his truck.

“It’s a bully move, if you ask me,” Kelly, 49, said. “Before they came, rent was manageable. I was never late. When they took over, it became out of reach.”

The “they” Kelly referred to is American Landmark, a major corporate landlord with roughly 34,000 units concentrated in 111 mega-complexes like Conrad across eight Southern states, particularly North Carolina, Florida, and Texas. Roughly two-thirds of its properties were purchased after the Covid pandemic began, and the company, with a private-equity structure that allows investors from all over the world to bet on the growth of its real estate portfolio, is now America’s 34th-largest landlord.

Based on a review by The Nation and Type Investigations of thousands of eviction records from dozens of American Landmark’s properties, as well as an interview with its CEO, Joseph Lubeck, it’s clear that the company’s management model inevitably leads to the frequent displacement of tenants like Kelly. At Conrad, the company is filing eviction notices at a rate nine times the national average. Dozens of filing rates well over double the national average were discovered across American Landmark’s portfolio. And though filings usually don’t result in an eviction if residents can come up with the rent in time, tenants and housing experts told The Nation and Type Investigations that they can worsen a cycle of debt and have a disastrous effect on people’s ability to rent a home in the future.

Over the past year, The Nation and Type Investigations spoke with 43 tenants who faced eviction cases filed by American Landmark for properties in Charlotte; Summerville, South Carolina; and Jacksonville, Florida. These tenants reported a wide array of issues they say led to their eviction cases—from steep rent increases to a blizzard of fees, including those connected to the eviction filings themselves.

“I feel like they’re predatory,” said Jeff Schuman, a tenant who was evicted in March from an American Landmark property in Jacksonville. “They can put a person out on the street with no recourse. You want to increase the homelessness rate because we’re short a couple of dollars? And I’m not condoning people not paying their bills. But sometimes people fall on hard times, and they should be given a chance.”

When I spoke with Joseph Lubeck, he vigorously denied that American Landmark’s practices are predatory, claiming that “most residents are very pleased” and that 65 percent renew their leases. But he confirmed that rent increases and displacement are part of the company’s strategy. “When we take over a property, the first analysis we do is: How much is the rent going to go up, and how many can afford to stay?” Lubeck said. “We typically raise the rent anywhere from $100 to $400, so some people are absolutely displaced. Some people paying $1,000 in a distressed apartment are not going to be able to afford the $1,400 we’re going to charge.”

Based on the company’s “modeling,” Lubeck said, only “55 percent of existing residents [are expected to] stay,” while the remaining 45 percent “move out.”

Whether they stay or get priced out, these tenants are also linked to a multinational conglomerate that profits from the displacement of people on the other side of the world. That’s because American Landmark is almost entirely owned by Elco, one of Israel’s largest corporations. For years, Elco, via its Electra Super Brand, has done extensive business in Israeli settlements in the occupied West Bank and East Jerusalem. Israeli settlements drive many thousands of Palestinians from their homes and are considered illegal under international law. Elco has also maintained deep ties to the Israeli military, including during the genocide in Gaza. The United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights has cited Electra Ltd. in its database of over 150 companies doing business in the settlements. In 2024, the American Friends Service Committee put Electra on its list of companies that “directly facilitate and enable human rights violations and violations of international law as part of Israel’s prolonged military occupations, apartheid, and genocide.” Meanwhile, in a podcast appearance that same year, an Electra executive described American Landmark as a “big winning card” for the company. (Elco and Electra Real Estate, the subsidiary that owns American Landmark, did not respond to requests for comment.)

For Kelly, though, there is little to celebrate in American Landmark’s success—a success predicated on driving tenants like him out of their homes. “They really messed everything up with that eviction,” he said of his life since the day he faced the judge. “It’s been a nightmare.”

In 2007, the Great Recession struck the United States. By 2010, at least 4 million families had lost their homes to foreclosure. But for Lubeck, the catastrophe was an opportunity. “I was very blessed in 2007, when there was an economic crisis,” he said in a 2023 interview with Ami Magazine. “It was a good time to buy.”

Over the previous decade, Lubeck, a former corporate lawyer from Philadelphia, had built an empire. In 1996, he spent “every penny” he had to buy a property in St. Petersburg, Florida, and launch Landmark Residential, and by 2008 he’d amassed nearly $2 billion in real estate assets. But it wasn’t enough. “I needed a bigger partner,” he said.

Around this time, Lubeck met the Salkind family, the owners of Elco. Elco was founded in 1949, a year after the state of Israel was created. Today, it is the country’s third-largest employer, with over 23,000 employees.

Landmark Residential “had an outstanding track record, a company that was delivering fantastic returns and knew how to operate effectively in the US,” Gil Rushinek, the chairman of Electra Real Estate’s board, said on an Israeli podcast in 2024. (His remarks have been translated from Hebrew.)

In July 2008, hoping to capitalize on Lubeck’s success (and on plummeting real estate prices), Elco purchased 90 percent of Landmark Residential. By 2011, Landmark had bought $564 million worth of real estate in the US. In the following years, the company repeatedly acquired massive portfolios, only to sell them off at a tidy profit and start again. By 2016, Lubeck and Elco had built a new $2 billion portfolio.

That year, they sold it all again, rebranding as American Landmark and snapping up thousands and thousands of units. Lubeck’s higher-ups at Electra have touted the way their partnership with Lubeck has become an international money-making machine. “In 2016, [with the creation of American Landmark], what we did was essentially transform Electra Real Estate from a traditional real estate company… into a private equity firm,” Rushinek said on the podcast.

Today, Lubeck serves as the CEO of American Landmark and the chairman of Electra America, under the ever-growing umbrella of Electra Real Estate. Despite supervising these billions worth of multifamily rental properties, Lubeck nonetheless cultivates a humble image.

“We still don’t view ourselves as corporate landlords,” Lubeck said. “Even though we’re very big and we have a big corporate structure.”

Meanwhile, Electra has landed contract after contract in the West Bank and expanded its ties to the Israeli military.

Electra has extensive links to West Bank settlements. In 2020, its subsidiary Electra Infrastructure landed a nearly $150 million deal with the Israeli Ministry of Transportation, the Jerusalem Municipality, and the contractor Moriah Jerusalem Development Company to construct four tunnels in Jerusalem, which are projected to help facilitate the movement of tens of thousands of settlers. According to the Who Profits Research Center, they will allow continuous travel from Ma’ale Adumim, an illegal settlement of nearly 40,000 people, almost all of whom are Jewish Israelis, to Jerusalem without any traffic lights. Hagit Ofran, a member of the Settlement Watch team at Peace Now, an Israeli anti-settlement advocacy group, said they will make the relatively cheap housing in Ma’ale Adumim more accessible for Israelis (at the expense of Palestinians).

“For the cost of a two-room apartment in Jerusalem, you can get a five-room apartment in Ma’ale Adumim. Now, because of the tunnel, if there is no traffic, you can go through Jerusalem in 10, 15 minutes,” Ofran said.

Electra Afikim, another subsidiary, is one of the largest public transit operators in Israel, with some 450 bus lines to its name. Many of those lines provide service to illegal settlements.

Furthermore, Electra is deeply intertwined with the Israeli military. It owns Electra Power, which has been “the exclusive gas supplier of the Israel Defense Forces and the country’s Police and Prison systems services for many years,” and supplies gas to illegal settlements, according to the American Friends Service Committee. Who Profits has found that Electra also helped to construct and maintain multiple Israeli military and police training facilities.

In 2024, well into the Gaza genocide, Electra Power’s CEO said on an Elco earnings call that “the IDF is a major client. We stand shoulder to shoulder with them in facing challenges and fulfilling missions. We are likely the only supplier that can say we’ve expanded our areas of deployment.… This is a great source of pride for us.”

While there are multiple degrees of separation between Electra’s business practices and American Landmark’s operations, companies that are even further removed have faced intense backlash as a result of their affiliation with Electra. For instance, the French retail giant Carrefour faced a global boycott for, among other things, its partnership with Yenot Bitan, an Electra-owned chain of grocery stores with branches in several illegal settlements, which contributed to Carrefour’s decision to close its branches in multiple Gulf states and culminated in widespread protests in France earlier this year.

In September, I connected with some American Landmark tenants that I had interviewed to inform them about the link to Electra and the illegal settlements. Among them was Mary Napier, a single mom who, like Kelly, had been evicted from the Conrad complex after her debts became insurmountable less than a year after she moved in.

“I’m not surprised that they’re doing people over here the same way they’re doing people over there, because we’re one and the same to them,” Napier, who sent American Landmark some $15,000 over the course of her tenancy, told me. “We’re like cattle to them, like dogs. And I still don’t have a place of my own. Me and my kids are still displaced. They don’t care about us. And they don’t care about those same people in Palestine.”

In a statement to The Nation and Type Investigations, Lubeck wrote, “Our company has no political views of any kind and our operation here is not guided or impacted by the conflict there, which is tragic for both sides.” Lubeck also said that Electra is far from the only entity reaping the rewards of American Landmark’s success: “Some of our biggest investors are Muslim countries from the Gulf, from Dubai, Abu Dhabi, Qatar, as well as Japan and Europe. So everybody is benefiting, and it has nothing to do with Jews or Israel or any of those things.”

Tenants like Kelly, however, appear to be excluded from that definition of “everybody.”

After American Landmark purchased Conrad at Concord Mills for $98.6 million in March 2022, things changed quickly, Kelly said.

There were a series of largely cosmetic alterations—brand-new light fixtures, cabinet doors, keyless door locks, faucet heads. (Walking through the complex, one feels this cosmetic focus palpably—winding roads lined by identical entryways with a uniform blue and white color palette blend into a Truman Show-like aesthetic.) The major appliances, like his fridge and his stove, were unchanged.

Then came the $400-a-month rent increase.

“They were basically saying, ‘Take it or leave it,’” Kelly said. Stephen Tuju, a former Conrad tenant of eight years who was facing an eviction case when I met him in February, told me that he, too, had seen a $400 increase. They were no exception: throughout American Landmark’s portfolio, tenants claimed that since Lubeck’s operation took over, costs have risen dramatically. Kaitlin Donahue, whom I met at an American Landmark building in Summerville, South Carolina, was paying $950 for a two-bedroom unit in the property seven years ago, before American Landmark’s takeover. Now she is paying nearly $1,600 for a one-bedroom.

“We had perfect rental history—never late, always on time,” said Jessica McIntire, another tenant in Summerville. Since 2022, her rent has jumped nearly $400; she received an eviction notice after struggling to pay the new sum. And she’s not alone, McIntire said: “The manager told me they were getting ready to evict 12 people this month” from the Summerville complex.

An internal 2011 presentation that the company (then called Elco Landmark Residential) put together provides insight into this strategy. It outlines its method of turning “working-class and young families” (described as the “broadest, most stable of Real Estate ‘food groups’”) into cash. According to the presentation, the company seeks out foreclosed or distressed complexes that can be acquired cheaply before renovating them.

These changes are then used to justify the rent increases American Landmark’s now-evicted tenants experienced, after which the company initiates a regime of “daily focus on rent collections” under which “management assumes rental increase of 20% annually over 3 years.” A December 2024 financial report indicated that American Landmark was keeping up with this goal: The company reported an average rent increase of 23 percent across the three investment funds that contain its properties. (In a statement, Lubeck said that those increases “may include many renovations on thousands of units within dozens of properties” and that once rents are “stabilized,” through the initial large rent increase, they typically rise 3 to 5 percent a year.)

Cities like Charlotte become especially attractive to vulture capitalists under this model. In a May 2022 post in Forbes, Lubeck highlighted four of the South’s “hottest markets”—ones in which annual rent increases had reached anywhere from 15 to 24 percent and that would be “likely to support continued rent growth.” Charlotte was first on his list.

He was right. According to the trade website Construction Coverage—which examined US Census and Department of Housing and Urban Development data—rents in Charlotte, where American Landmark owns roughly one in every 85 units, rose by 17 percent in 2024, more than in any other major US city.

Lubeck was emphatic that the impact on tenants was minimal. “The rent increases do not lead to more evictions. Some people, more than usual, may move out,” he told me (later quipping that “if [tenants] choose to buy a BMW and not pay their rent, that’s up to them”). “But we’re not causing evictions. We’re replenishing rental stock.”

Yet The Nation’s and Type Investigations’ review of thousands of eviction filings tells a different story.

“It was one of the worst experiences I’ve had in my life,” said Jeff Schuman, describing the day he was thrown out by American Landmark. “I left all kinds of furniture there, thousands of dollars’ worth of stuff I had to leave because they were on top of me,” he continued. “I was like, ‘I don’t have anywhere to go and have a small child.’ They don’t care. They’re like slumlords.”

In the 2011 presentation, American Landmark made it clear that these evictions are key to its business model. At each new property, the presentation said, the company must “clean up rent roll by evicting delinquent or non-paying tenants and attracting higher quality tenants.”

According to Lubeck, American Landmark’s apartments house about 70,000 tenants. Based on his assessment that 45 percent of a property’s original tenants won’t survive an American Landmark acquisition, around 30,000 people left their homes after the company took over.

Many of those departures were prompted by eviction filings. In order to start the process of kicking a tenant out, landlords submit an eviction filing in court (though most of these, again, do not result in an eviction). Reliable data on evictions at the national level is nearly impossible to produce, but one of the best estimates comes from the Eviction Lab at Princeton University, which calculates an average eviction-filing rate based on a sample of US cities and states. In 2024, that rate was about 7 percent—in other words, for every 100 units in the sample, landlords filed about seven evictions in court. The highest rate for any of the areas the group tracked was 24 percent. (This formula includes tenants who were filed against repeatedly.) In the first half of 2025, records show, Conrad at Concord Mills was on track for an eviction-filing rate of 67 percent, more than nine times the national average. This was no fluke: A search on the North Carolina court-records website shows that American Landmark filed 244 eviction cases against tenants at the complex in 2024. Using Eviction Lab’s formula, we divided this sum by 357—the total number of units in Conrad at Concord Mills—which yielded an eviction-filing rate of 68 percent.

These stark filing rates are partly enabled by the fact that American Landmark’s portfolio is concentrated in states with very little infrastructure in place to protect tenants from exploitation. “Republican red states are very landlordist,” said Rushinek, Electra Real Estate’s board chair, in the 2024 podcast. “In free-market capitalism, there are few protections for the tenant. If you want to evict a tenant in New York, you will have a lot more of a challenge than evicting a tenant in Florida.”

But American Landmark’s eviction-filing rate stands out even in comparison with those of other landlords in these states; for instance, in 2019, the last full year that the Conrad complex was under its previous ownership before a temporary Covid-era eviction moratorium, the owners filed at a rate of 16 percent—indicating that since American Landmark took over, the eviction filing rate at the complex has more than quadrupled.

The Nation and Type Investigations were able to identify at least 29 American Landmark properties at which, in the first half of 2025, the eviction-filing rate was more than twice Eviction Lab’s average, and that number grows to 41 American Landmark properties when the data from 2023 and 2024 is included. In a majority of those 41 properties, the rate has been more than double the average in multiple calendar years. All eight states in which American Landmark operates had at least one such property, and they were spread out among at least 28 different municipalities: The rate was 48 percent at a complex in Marietta, Georgia; 58 percent at Kaitlin Donahue’s complex in Summerville, South Carolina; and 70 percent at a Houston complex, all of which contain hundreds of units.

Additionally, many eviction filings were concentrated in what Lubeck identified as American Landmark’s “hottest markets.” In the first half of 2025, the six American Landmark complexes in Charlotte for which we could obtain eviction data had an average filing rate of 51 percent—seven times the national average. Though there were many tenants in Charlotte filed against repeatedly in this period, American Landmark nonetheless threatened about 450 different people with eviction—roughly one tenant for every five units the company owns in the city. One complex in Charlotte, Celsius Apartment Homes, had the highest eviction-filing rate recorded for any of American Landmark’s properties in the first half of 2025, at 82 percent. When I visited that complex, multiple units had eviction notices wedged in their doors. (“You walk through here like ‘Damn!’” one tenant at Celsius, who was evicted this year, told me at their apartment.)

I posed these figures to Lubeck. “There’s no way that that [filing] data is accurate. It just does not happen, would never happen,” he said. “We’re not in the eviction business.” Later, he acknowledged that “there may be 50 evictions filed in a 200-unit property.” The company tends to file evictions once rent is 10 to 15 days past due, Lubeck said. But he emphasized that American Landmark dismisses the vast majority of eviction cases because most tenants pay the overdue balance before their court date, and he claimed that the filings alone do not affect a tenant’s credit report. In other words, once American Landmark dismisses the case, there’s no harm done.

Justin Tucker, who heads the housing unit at Legal Aid of North Carolina, disagrees, noting that eviction-filing records are publicly accessible. “There are landlords across the state that will not rent to you because you have an [eviction] filing—point blank, period,” he said. In most states where American Landmark’s tenants live, including North Carolina, there is no way to remove an eviction case from a tenant’s record, meaning that people like Kelly will likely find it more difficult to obtain housing for the rest of their lives. (“The negative impact…is a result of the resident’s failure to make timely payments,” Lubeck said.)

At least six tenants in three states, including Kelly, said they discovered the depth of this black mark the hard way. Jessica McIntire, from the Summerville complex, had a typical experience: As American Landmark pursued its most recent eviction case against her and her husband, the couple began applying for apartments in the neighboring town. “We were rejected” for all of them, she said.

In early 2024, Mary Napier’s house near Charlotte went up in flames. Already a single mother to a toddler, Napier was also pregnant. She needed a place to stay—fast. The Conrad complex seemed like a lifeline, its $1,400 base rent just barely within her budget. She jumped at the opportunity and moved in that April. “It was almost too good to be true,” she told me when I visited her at her apartment in February 2025. By the next month, she would be evicted.

Though Napier’s short-lived tenancy began after the rent increases had already hit the Conrad complex, her case is nonetheless emblematic of the pattern, described by many tenants, of costs at American Landmark properties spiraling out of control. First, there were the fees that many said contributed to American Landmark’s filing an eviction against them. Almost all of them are mandatory: from a $100 “technology package” of Wi-Fi and cable to a valet trash service, pest control, fees for the complex’s amenities, and often many others. All the tenants I spoke with said the fees totaled at least $150 per month.

At least 18 residents, in seven different buildings, told me that these costs came as a surprise to them; they reported feeling rushed through the lease-signing process or misled as to what they would owe, so that when their first bill came around, it was as though they’d been hit with an instant $150 or more rent increase. When asked about these complaints, Lubeck said that the fees are included in addendums to the tenants’ lease agreements. “Everything is disclosed up front and in writing. It’s very clear,” he said, even as he admitted that he’s “sure there are cases where people don’t know what they sign.”

Napier was one such tenant. “I could cry right now,” she said, her daughter at her side. “When the first month came around and it was almost $1,600 [because of the fees], I was like, ‘I’ve been duped.’ I knew I was going to struggle. Once you start struggling, they jump on your neck. It makes you feel hopeless.”

Then there were the costs surrounding the nonnegotiable, roughly $100-a-month cable and Wi-Fi package that all American Landmark tenants enroll in and that cannot be paid separately from their rent. Seven tenants claimed that this package comes with an aggressive side effect—once they fell behind on rent, American Landmark disconnected the cable and Internet service. “That felt a little more personal,” Napier said.

When this happens, according to records provided by multiple tenants, American Landmark continues to charge as though the services were still connected. In e-mails provided to The Nation by Stephen Tuju, the former Conrad tenant, American Landmark justified this by stating that “while your internet services may currently be suspended, the Cable and WiFi are included as part of the mandatory concierge package in your rent. These charges cannot be waived.”

At least three tenants—Napier, Tuju, and Christopher Dawkins, all at the Conrad complex—reported that after their Wi-Fi was disconnected, a new $75 “reconnect fee” appeared in their monthly bill. This meant that not only were they still being charged for nonexistent WiFi, they were also being charged, in the same month, to turn it back on. (Napier provided The Nation with her January 2025 bill, which showed both the reconnection fee and the technology package in her list of charges.)

“They’re using the [technology package] as a tool of debt collection to coerce you to pay everything,” Tuju told me. After he complained, American Landmark inexplicably notified him that it would “adjust” the fee to $25. “There’s something wrong about that,” Tuju added. Lubeck confirmed that the company’s policy is to disconnect the technology package when tenants are late with the rent. In Tuju’s case, “it’s possible someone made a mistake,” Lubeck said, but “everything is established and fair across the board.”

Finally, an eviction filing itself brings extra fees. Peter Hepburn, the associate director of Eviction Lab, told me that on average, landlords charge tenants roughly $180 every time an eviction is filed. Napier was charged a $69.50 late fee on top of $266 in fees to partially cover the cost of American Landmark’s own attorneys. Other tenants told me their court fees climbed as high as $400.

“That’s why I’m still trying to play catch-up,” said Dawkins, a 30-year-old tenant at Conrad at Concord Mills, in February. For each of his four eviction cases, he told me, American Landmark charged him around $300 in fees. “I got kids, too. When you got a lot going on, every dollar counts.”

But even as tenants pay the price, the model is working for the landlords. By the time of Electra’s December 2024 report, two of American Landmark’s investment funds had distributed a combined $890 million to investors—which includes money sent back to Electra itself—since 2018. Electra projected that one of those funds would more than double the company’s initial investment. And those hundreds of millions of dollars are then funneled into a machine of Elco-owned Israeli corporations that are helping to wreak havoc on Palestinians.

It was nearing 6 pm at the Isaac, an American Landmark property in South Carolina that I visited in February. The day’s light was fading fast.

I was on the second floor of one of the many 12-unit entryways in the development, surrounded by the gray siding typical of most of the American Landmark complexes I visited. I was hoping to find a woman named Shania Jones. When the door swung open, a young couple greeted me. I asked if Jones lived there. The woman’s eyes lit up. “No, but…” she said, turning to rummage through a bin behind her, “we still get her mail.”

It was the fourth time that day when, rather than finding the tenant facing eviction, I was instead met with a different, young family. Leftover mail was often the last trace of those who had fallen prey to the company’s promise to “clean up” their properties to “attract higher quality tenants.”

There were also traces of soon-to-be-former American Landmark tenants at the Mecklenburg County Courthouse, where Charlotte’s eviction cases are adjudicated. When I visited on February 10, tacked up on bulletin boards were names of 44 tenants across 36 eviction cases among the company’s 2,400 units in the city. Two days later, there were 18 more cases with 24 more names.

Among those cases was Napier’s. She had never been to the courthouse before, and said she missed the start of her hearing because she was accidentally sitting outside the wrong courtroom. By the time she realized her mistake, the judge had ruled against her. At an eviction court hearing for another tenant later that day, an American Landmark lawyer would argue that “personal hardships, financial hardships, just life hardships, are typically not legal justifications [against an eviction].”

When I followed up in August with the American Landmark tenants I had spoken with earlier, at least seven had moved back in with family or friends—largely into spaces not meant to hold so many people, in a sign that the evictions filed against them may have severely restricted their options. Napier, her kids, and her mother, for example, moved into her sister’s three-bedroom townhouse this summer, bringing the number of residents there to seven. It’s her third home in two years, and in that time she’s gone from a three-bedroom house to sharing a single room with her children. “I’m living out of bins, out of bags, out of suitcases,” she said. “I don’t know what’s next. It’s kind of dark.”

Diron Kelly, meanwhile, is a warning of what could happen next. With nowhere to go after his eviction, he found his way to a nearby shelter. “I tried, but there was [nothing] available,” he said. “It just didn’t work out.” He spent months homeless, in his truck, before eventually moving to Georgia, where his sister had some extra room.

Lubeck said that while “a number of people are not going to be able to afford what we do” and that he “can’t sugarcoat that,” it “doesn’t mean they have to go homeless.”

Meanwhile, Lubeck’s parent company is profiting from the displacement of Palestinians living under occupation 6,000 miles away.

In August, I contacted the United Nations Human Rights Office to ask about the implications of a circumstance like this, in which a company the office has flagged for involvement in Israeli settlements has a large US subsidiary profiting off tenants like Kelly. A spokesperson, Thameen Al-Kheetan, told me, “States should implement their duty to protect and ensure respect for human rights, including by setting out clearly the expectation that all business enterprises domiciled in their territory and/or jurisdiction respect human rights throughout their operations.”

The chances of that are slim. President Donald Trump is not only a landlord but leads a country that has long helped the Israeli government and its corporate partners like Electra to evade the consequences for their role in perpetuating the settlements and the ongoing genocide in Gaza. (For example, the United States was one of the few countries that voted against allowing the UN to provide annual updates to the database of settlement-linked businesses in which Electra’s name appears.) And by Electra’s own admission, the company has deliberately concentrated its US operations in Republican-controlled states that are especially unlikely to pass anti-landlord legislation.

Unless this changes, there are sure to be more people displaced at the hands of this conglomerate every year. More evictions. More illegal settlements. More profits for Electra and American Landmark.

More mail left behind in a home that used to be someone else’s.

More from The Nation

The story ofhis landmark case reminds us of how powerful a popular front of socialists and liberals can be in protecting our civil liberties.

All too often, when a family can’t afford safe housing, the solution child welfare services offer is taking away the children.

As Trump escalates his war on civil society, will liberal foundations join the fight to defend democracy?

The state of the world has been looking dark. Helping our fellow human beings is one way to add some light.