The economic force is often seen as a barometer for a nation’s mood and health. But have we misunderstood it all along?

Donald Trump holds a big and a small box of Tic Tac to illustrate inflation outcome during a town hall event at Dream City Church in Phoenix, Arizona, on 2024.

(Jim WATSON / AFP)

It was once natural to think that prices rise constantly, no matter how many new ways are found to make more crap more cheaply. Inflation was just a part of life in a capitalist society where growth was expected every quarter. When it got a little too high, the main culprits—reckless government spending, low unemployment—had come to seem self-evident, too. And for some reason, the consensus was that when inflation exceeded 2 percent—the target rate of the US Federal Reserve and most other central banks—the Fed was supposed to raise interest rates, “cooling” the economy, destroying jobs, and even causing a recession in the process. The educated lay reader might imagine a big knob somewhere that the Fed chairman (Jerome Powell, for now) could turn to increase or decrease the economy’s temperature and make life a little harder, or a little easier, for everyone as needed.

Books in review

Inflation: A Guide for Users and Losers

During and after the Covid-19 crisis, however, when prices surged internationally at rates that had not been seen in rich countries for 40 years, some unfamiliar factors at work also posed surprising challenges to these received ideas. In June 2022, when the theoretical basket of goods in the Consumer Price Index was costing US consumers 9 percent more than it had 12 months earlier, and former treasury secretary Larry Summers proposed that the Federal Reserve could only bring that inflation under control by engineering massive unemployment, there was an unusual level of public debate. What needed to be done depended on what you believed was causing inflation in the first place. Summers blamed the Covid stimulus spending and all those bored, homebound consumers who spent their checks on more stuff. Together with the pandemic-related supply-chain problems, it looked like a classic case of too much money chasing too few goods. But Summers was challenged by the economist Paul Krugman, among others, who guessed that the inflation would prove to be transitory. Crashing the party from the left, the German economist Isabella Weber pointed to signs of corporate price-gouging (“greedflation”) and sparked a particularly heated debate, on Twitter and elsewhere, by advocating for price controls.

Inflation became one of the defining issues of the 2024 US presidential election—perhaps the decisive one—and it continues to haunt the current regime, its delusional tariffs scheme, and its more recent attempt to orchestrate a presidential takeover of the Fed. Mark Blyth and Nicolò Fraccaroli likely wrote their wide-ranging new critique, Inflation: A Guide for Users and Losers, before the election, but it effectively uses recent experiences and debates as a kind of lever to pry open their subject’s history and theory. Inflation presents the basics—how price indexes are made, the main historical episodes and schools of thought, what makes hyperinflation happen, the effects of inflation and its remedies on different classes—while also carefully deconstructing familiar arguments, often rethinking history in light of recent events. Blyth and Fraccaroli find that the supposed lessons of the past—especially the idea that inflation is best understood as a monetary problem that can best be addressed by central banks raising their interest rates—might not apply in post-neoliberal times of deglobalization and climate crisis. Whatever the economic future may bring, their timely intervention in the inflation debate provides a fresh perspective on the end of an era.

Borrowing a famous phrase from the Italian filmmaker Sergio Leone by way of Fabio Panetta, the governor of the Bank of Italy, the authors distinguish the “good” inflation that central banks are supposed to maintain from the “bad” and the “ugly” kinds. Good inflation is said to be moderate and stable, just a side effect of economic growth. Bad inflation is caused by temporary factors like supply-chain shocks that affect broad sectors of the economy. Inflation gets ugly when, as economists say, “expectations” get “de-anchored.” If high inflation endures long enough, the argument goes, it becomes a self-fulfilling fear: Businesses start to raise their prices in anticipation, shoppers rush to buy before the sticker shock sets in, workers start asking for that raise, and all of this drives prices higher faster. Blyth and Fraccaroli usefully criticize this model right down to the surveys that are supposed to reveal “expectations,” and especially the specter of a “wage-price spiral,” which presupposes that workers are able to fight continuously for higher wages.

In this sense and in many others, the authors emphasize that inflation is not just one “thing.” Most fundamentally, perhaps, it can be measured in different ways. Understanding how price indexes are used to combine many prices into one “inflation” number, and understanding as well some basic economic factors—the difference between “core” and “headline” inflation, the difficulties of pricing owner-occupied housing or changes in consumer behavior, and so on—is probably essential for engaging in debates about the causes of inflation and the sometimes significant gaps between everyday experiences and the numbers in the news. Measurement is also important because it directly determines policy.

The practical idea about inflation that Blyth and Fraccaroli are most determined to dispute is the notion that the best response to high inflation is always for a central bank to raise interest rates. They offer a vigorous critique of the reasoning behind this idea and the historical narrative that is used to support it, what they call “That 70’s Show.” The decade looms so large in how we think about inflation that their book returns to it repeatedly from different points of view. The authors begin at the end of the decade, with the supposed solution to high inflation, and dig back roughly in reverse chronological order, turning to earlier attempts to solve the problem, as well as to its causes and the concurrent rise of monetarist thought. The end of the story is Paul Volcker’s famous decision, as chairman of the Fed, to fight very high inflation (on the order of 13 percent) with very high interest rates (around 20 percent), intentionally tanking the US economy. The so-called Volcker shock caused an immediate recession and made Volcker himself a legend: widely loathed at the time but a symbol of central bank independence for his successors, the heroic founder of the period of macroeconomic stability that eventually followed. Yet Blyth and Fraccaroli’s interpretation of what they call “Volcker’s hammer” evokes less Thor than the proverb about everything looking like a nail. They survey the harms of Volcker’s policy before casting doubt on its necessity and even its effectiveness. Driving up unemployment to nearly 11 percent by 1982—a rate not topped until the Covid pandemic—crushed the bargaining power of workers. The high interest rates also brought car and home sales to a halt, sparked the savings-and-loan crisis, and raised the borrowing costs for city and state governments. But its effects were particularly catastrophic for those developing countries that held huge loans in dollars, such as Mexico, Argentina, and Brazil, because the policy increased the value of the dollar relative to their own domestic currencies to levels that made the loans immediately unaffordable. The authors describe the result as “a lost decade of growth for all of Latin America, and a pile of debt now so large that Latin America can never conceivably pay it back.”

This cautionary tale would be idle if there were no other ways to fight inflation than by raising interest rates. One alternative that Blyth and Fraccaroli consider repeatedly is obvious, drastic, and outrageous to most economists: If the problem is rising prices, then governments can just control prices. The authors often return to a great historical precedent here that is mostly forgotten except by true nerds: In 1971, Richard Nixon simply announced that he was “ordering a freeze on all prices and wages throughout the United States.” It is hard now to believe that an American president could do that, and it turned out to be a fleeting episode, but its failure, the authors argue, was more political than economic. (As originally implemented, Nixon’s freeze was mandatory and effective; what failed was a later phase of the program in which compliance was voluntary.)

While analyzing recent examples of price controls and related policies—despite its name, the German Gaspreisbremse, or “gas price brake,” was not a price control but a subsidy to consumers—Blyth and Fraccaroli also discuss alternatives, including windfall taxes on excess profits and the use of buffer stocks to bring down prices. If the causes of inflation are multiple and not simply monetary, the best approach may be a politically coordinated package of measures, not unilateral action by a central bank.

The book’s chapter on hyperinflation, looking at Venezuela, Zimbabwe, and Argentina before turning to the classic example of the early Weimar Republic, similarly criticizes the idea that hyperinflation is caused by governments just printing too much damn money. The root causes of hyperinflation are typically multiple and unique to each specific case: In Venezuela, for example, the origins of the hyperinflation that is still decimating the country and driving a mass exodus of its population can’t be understood as a simple consequence of massive public spending on social programs. Blyth and Fraccaroli provide a complex explanation that involves a confluence of factors, including the usual suspects (“too much money” and a “classic” wage-price spiral) but also distinctive shocks, above all from the high price of oil and a series of apparently contingent political decisions.

It may be in the nature of criticism to distinguish and historicize. Sometimes it’s important just to say that things are complicated. That seems to be the message of the last chapter of Inflation, “Are Inflation Wars Class Wars?” The authors answer in the affirmative: Inflation hurts low-income people disproportionately and most painfully, simply because they spend more of their income on consumer goods and have less to spare. But fighting inflation by raising interest rates also hurts workers by design, since the whole point is to raise unemployment. The book’s class-struggle interpretation of inflation, however, also involves many “buts” within “buts.” Inflation also benefits people in debt, according to the so-called Fisher effect, because the value of the debt goes down. Some of the “winners” of inflation are probably young middle-class people with new fixed-rate mortgages. Conversely, raising interest rates to fight inflation benefits the creditor class and sometimes compensates them for the inflationary depreciation of their wealth. Alongside the eternal conflict between businesses trying to protect their profits and workers trying to protect real wages—a conflict that can be exacerbated by inflation—the authors also analyze the different concerns of banks and other kinds of firms, providing a variegated view of the interests of the ruling classes.

Inflation takes a surprisingly broad historical and comparative perspective for such a concise and accessible book. It is not specifically focused on the current political situation in the United States and the threat of inflation due to tariffs, a threat that will only be exacerbated if a MAGAfied Fed tries to rescue a bad economy by cutting rates too fast. But the authors do include geopolitical “deglobalization” among their reasons to believe that inflation will remain a threat and that we need to think differently about it now. They are cautious in their speculation about the longer term: After all, until recently, inflation seemed to be under control in much of the world. If its recent return was largely due to supply shocks and price-gouging, maybe we will simply return to the mean. In the long term, although we tend to imagine the past as a time when everything was cheaper and “a buck was still silver,” as Merle Haggard sang in 1981, the normal trend of capitalism should be strongly deflationary, as stuff does constantly get cheaper to make and move around.

Yet Blyth and Fraccaroli ultimately see greater reasons to believe that inflation will take new forms in a “post-neoliberal” world. The low inflation of the past several decades was not due simply to omniscient fiscal policy; instead, it was largely due to the incorporation of China into the global economy. Not much keeps prices down like massive amounts of cheap labor—but any day now, it seems, we are going to learn what happens when that world comes to an end. Beyond the prospect of a trade war, there is the fact that the planet is still burning. Inflation may not be the most gruesome or obvious consequence of the climate crisis, but it seems safe to predict that climate change will raise the costs of food and shelter. We may see persistent new types of inflation that are no longer caused by the usual suspects, and against which the old central-bank playbook may not work at all, or work only in tandem with other tools, probably in other hands. The merely “bad” inflation that we saw as a consequence of Covid-19 and the war in Ukraine may prove to be a taste of ever uglier things to come.

More from The Nation

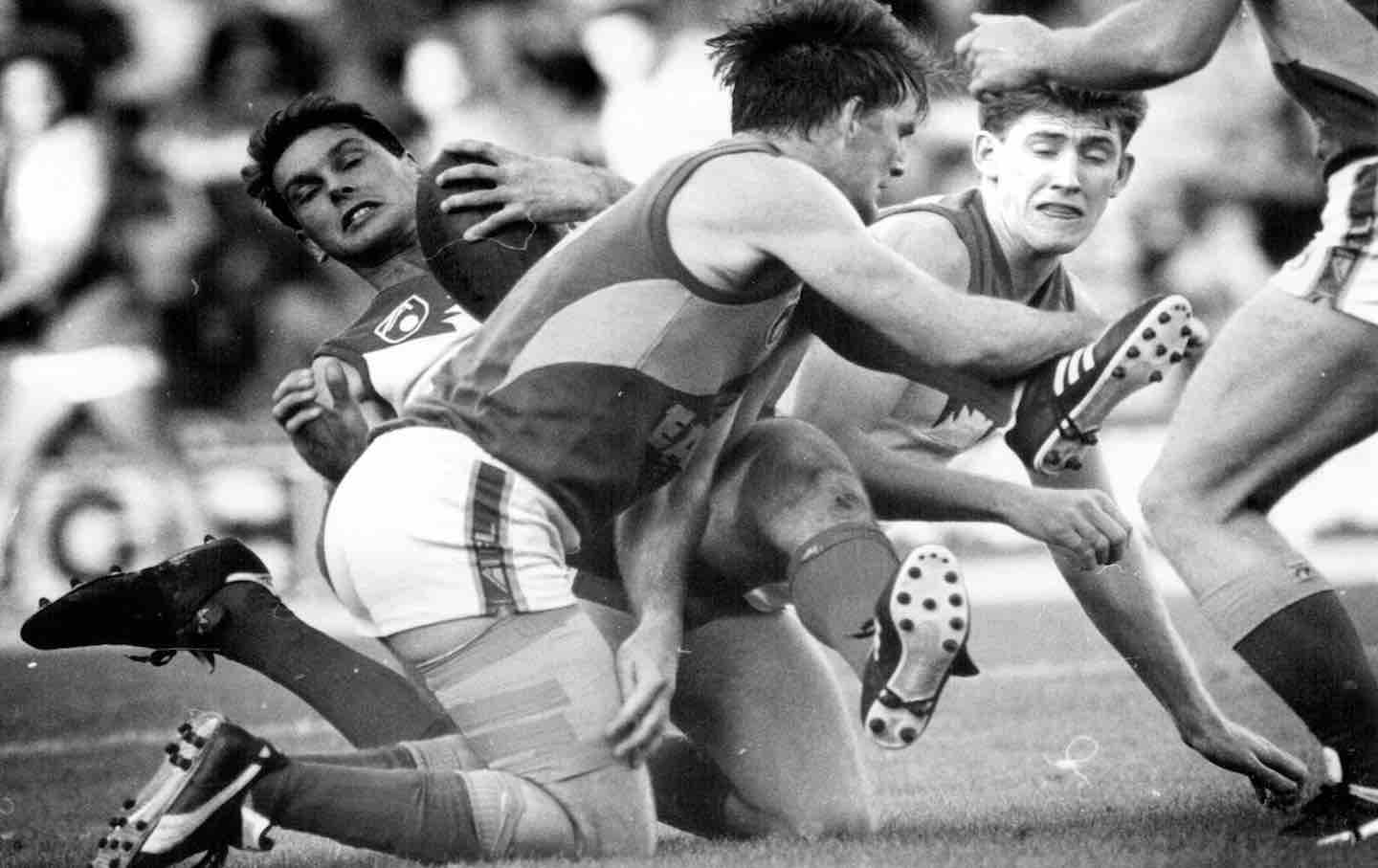

In The Season, Helen Garner considers the zeal and irrationality of fandom and her country’s favorite pastime, Australian rules football.